मूर्खः परिहर्तव्यः प्रत्यक्षः द्विपदः पशुः । which means.. A stupid person must be avoided. He is like a two-legged animal in-front of the eyes.

Comparing

the Sanskrit and the English versions, the difference is

conspicuous. Only 5 words in the Sanskrit version but so many in the

English version. We also explained in the last article that this

enormous shortening has been possible due to the notion of vibhakti.

(Have a look at the last article

to understand the mechanism of this shortening.) But we didn’t explain

in full, the power that this innovative concept of vibhakti wields. In

this article, we will look at the magic that is possible in a language

whose sentence structure is based on this notion. And, not to mention,

this notion of vibhakti lies at the heart of Sanskrit Grammar. We will

also investigate how the vibhaktis enable one to

compose verbless sentences in Sanskrit, which is not possible in

English! Let’s get into translating some hardcore Sanskrit.

Comparing

the Sanskrit and the English versions, the difference is

conspicuous. Only 5 words in the Sanskrit version but so many in the

English version. We also explained in the last article that this

enormous shortening has been possible due to the notion of vibhakti.

(Have a look at the last article

to understand the mechanism of this shortening.) But we didn’t explain

in full, the power that this innovative concept of vibhakti wields. In

this article, we will look at the magic that is possible in a language

whose sentence structure is based on this notion. And, not to mention,

this notion of vibhakti lies at the heart of Sanskrit Grammar. We will

also investigate how the vibhaktis enable one to

compose verbless sentences in Sanskrit, which is not possible in

English! Let’s get into translating some hardcore Sanskrit.

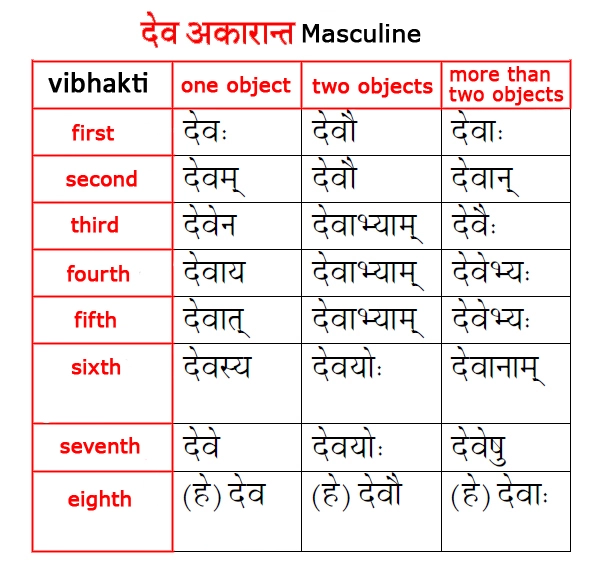

Let’s

take up a typical word, say देव, as an example. Given below is a table

that lists this same word देव but with some modifications. Here we have

24 different forms of the word देव | Each of these forms is called a vibhakti of देव |

Remember

this table from school Sanskrit ? It is afterall not as annoying as

many feel in the school. In fact, it is very powerful! Let’s discover

its power.

Now let’s get back to our Q&A format.

Q)

Yes! I do remember these horrible tables from school. They used to

force-feed these into our brains. I remember, we were expected to

memorize around 30 such tables and had to vomit out one of them in the

final exams.

A) You are right. The way these are taught in the school course of Sanskrit is hopeless. Memorizing these tables without comprehending their power is like memorizing Thermodynamic tables of Specific Heats without comprehending the Laws of Thermodynamics. In this article, we shall focus on the concepts behind these rather than memorizing them. Now smile!

A) You are right. The way these are taught in the school course of Sanskrit is hopeless. Memorizing these tables without comprehending their power is like memorizing Thermodynamic tables of Specific Heats without comprehending the Laws of Thermodynamics. In this article, we shall focus on the concepts behind these rather than memorizing them. Now smile!

Q) Hmmm  …concepts ? So what are they ?

…concepts ? So what are they ?

A) As mentioned in the last article, in general, a word in Sanskrit represents property(s).

A) As mentioned in the last article, in general, a word in Sanskrit represents property(s).

Agni,

one of the 33 devas mentioned in Vedas. Devas refer to terrestrial

things of high excellence. Here is a list of all the devas. 8 Vasus

(Earth, Water, Fire, Air, Sky, Moon, Sun, Stars/ Planets) that form

components of universe where we live, 10 Life Forces in our body (Prana,

Apana, Vyana, Udana, Samaana, Naga, Kurma, Kukala, Devadatta) and 1

Soul called Rudra, 12 Aditya or months of year, 1 Vidyut or

Electromagnetic force that is of tremendous use to us. 1 Yajna or

constant noble selfless deeds done by humans.

Here, देव represents (the property of) being of great excellence or being heavenly. But,

in spoken language, we always refer to objects and not properties. (The

object being referred to need not exist in the real world. It is

sufficient if it exists in the speaker’s imagination.) So we need a way

to force the word देव, to represent an object rather than a property.

That way of forcing a word(which represents a property) to represent an

object is called vibhakti. Let us now settle on the

agreement that (x|y) would stand for the vibhakti-form of देव in the

xth row and yth column of the table. So, (6|3) = देवानाम् and (1|1) =

देवः |

Here are our rules.

Rule1 |

A vibhakti-form of a word always denotes an object having the property

that the respective word represents. So, whenever in a sentence you

come across, say, देवस्य or देवैः or देवेषु, it means that an object

having the property of being of great excellence exists.

Rule2 | Each vibhakti-form in the table carries 3 pieces of info with itself viz.

- the number of objects (whether singular, dual or plural ?)

- the number of the vibhakti (whether it is the first vibhakti or third or eighth ?)

- the gender of the object (whether it is a male object or female or neutral ?)

So, (6|3) = देवानाम् carries the info that there are more than 2 masculine objects of sixth vibhakti, having the property of being of great excellence.

Rule3 | Every sentence has an action involved in it. (This is a general rule applicable to any language.)

Rule4 | Objects having the same vibhakti point to the same object. (We have already seen an awesome application of this rule in the last article.)

Having noticed these 4 rules, now let’s understand the meaning of each vibhakti in the form of the extended table below.

Explaining

vibhaktis. The text in blue explains what it means when a word in a

sentence appears in the vibhakti number of that row.

Explaining vibhaktis again, but this time with a different example !

Now, lets take up some sample sentences and try to translate them. Here they are.

- रक्तनेत्रः भेतव्यः।

- उपदेशः मूर्खानाम् प्रकोपाय ।

- रथेन यात्रा न मनोरथेन।

Let me also give you the closest English words corresponding to each of the words involved.

- रक्तनेत्र = (the property of) having red eyes

- भेतव्य = (the property by which one) must be feared

- उपदेश = (the property of) directing in a particular direction/way

- मूर्ख = (the property of) being stupid

- प्रकोप = aggression, hoslility

- रथ = (the property of) advancing towards something

- यात्रा = (the property of) going in a regulated manner

- न = not (Note: This word does not represent a property nor do vibhakti-forms of it exist. Such words are called अव्यय)

- मनोरथ = (the property of) going towards something but only in mind

Q) Before starting to translate, can you give me general guidelines for translating them.

A) Sure!

A) Sure!

- The first thing you must do while translating any Sanskrit sentence is to identify whether any words in the sentence exist in their vibhakti-forms or not. Those words which exist in a vibhakti-form represent objects, by Rule1! (Need not be physical objects. They may be abstract objects in the imagination of the speaker!)

- For the words that exist in a vibhakti-form, identify the 3 pieces of info mentioned in Rule2

- Rule3 assures us that there is bound to be some action involved in the sentence! Identify that action and guess the relation of each word with that action using the blue text of the extended vibhakti tables pasted above. When no action is explicitly mentioned, then it is the action of existing of the object denoted by the words of the first vibhakti.

- Apply Rule4, if applicable.

And lo, you have the translation.

Translating Sentence 1

रक्तनेत्रः भेतव्यः।

(1|1) (1|1)

(1|1) (1|1)

- Applying Rule1. From above, रक्तनेत्र = (the property of) having red eyes, but since the sentence contains रक्तनेत्रः and not रक्तनेत्र, by Rule1, we conclude that रक्तनेत्रः = an object/person having red eyes. Similarly, भेतव्यः does not represent a property rather it denotes an object/person who must be feared.

- Applying Rule2. We try to identify the grammatical info carried by these words. Both the words are of the form (1|1) of the देव table. So the info they carry is that each of रक्तनेत्रः and भेतव्यः denote single masculine objects of first vibhakti.

- Applying Rule3. We try to identify the action involved in the sentence. Since the action is not explicitly mentioned, it is the action of existing of objects denoted by the words of the first vibhakti viz. रक्तनेत्रः and भेतव्यः |. And from the vibhakti table above, both रक्तनेत्रः and भेतव्यः perform that action. (See the top-most blue line in the देव table.) Hence, the objects denoted by रक्तनेत्रः and भेतव्यः exist. This existence itself is the action.

- Applying Rule4. Both the words have the same vibhakti viz. first vibhakti, hence they denote the same object. So, रक्तनेत्रः and भेतव्यः are the same objects and not different objects.

So,

the sentence means that the person who has red eyes and the person

who must be feared are one and the same. So the sentence translates to One who has red eyes must be feared. Notice the difference in length. English version has 8 words while the Sanskrit version has only 2!

Translating Sentence 2

उपदेशः मूर्खानाम् प्रकोपाय ।

(1|1) (6|3) (4|1)

(1|1) (6|3) (4|1)

- Rule1 says, since all the words appear in a vibhakti-form, each word denotes an object.

उपदेशः = something that directs = advice, instructions

मूर्खानाम् = someone who is stupid

प्रकोपाय = hostility (seen as an object) - Rule2 instructs us to identify the 3 pieces of info, viz.

उपदेशः denotes a single masculine object in first vibhakti (1|1)

मूर्खानाम् denotes more than 2 masculine objects of sixth vibhakti (6|3)

प्रकोपाय denotes single masculine object of fourth vibhakti (4|1) - Rule3 asks

us to infer the relation of each object with the action by looking at

the blue text in the vibhakti table. The action is “existing”, from Rule3.

उपदेशः = (1|1) implies that advice is performing the action of existing, that is, advice exists, which means some advice is being given by someone.

मूर्खानाम् = (6|3) implies that प्रकोप belongs to the मूर्ख persons being refereed to. प्रकोपाय = (4|1) implies that the action (of existing/giving of advice) helps/intensifies प्रकोप | - Rule4 not applicable.

Hence the sentence translates to Giving advice intensifies the hostility of stupid people.

Translating Sentence 3

रथेन यात्रा न मनोरथेन।

(3|1) (1|1) (nil) (3|1)

(3|1) (1|1) (nil) (3|1)

- Rule1 says, since all the words, except न, appear in a vibhakti-form, they denote an object.

रथेन = a chariot

यात्रा = journey or travel

न = not

मनोरथेन = an imaginary chariot in mind - Rule2 instructs us to identify the 3 pieces of info, viz.

रथेन denotes a single masculine object in third vibhakti (3|1)

यात्रा denotes a single feminine object of first vibhakti (1|1)

न does not denotes any object

मनोरथेन denotes a single masculine object of third vibhakti (3|1) - Rule3 asks

us to infer the relation of each object with the action by looking at

the blue text in the vibhakti table. The action is “existing”, from Rule3.

रथेन = (3|1) implies that the chariot is instrumental in performing the action

यात्रा = (1|1) implies that journey exists, that is, journey is being done

न = (nil) negates the meaning of the word that comes after it

मनोरथेन = (3|1) implies that the chariot of mind is instrumental in performing the action - Rule4 does not give any new info.

Hence, the sentence translates to Journey is done by a (real) chariot, not by a chariot of mind.

Q)

I really enjoyed! But there is some feeling of uncertainty lingering in

my mind. In the sentence, रथेन यात्रा न मनोरथेन। why did you say that

Rule4 does not give any new info ? I mean, रथेन and मनोरथेन, both have

the same vibhakti viz. third vibhakti, hence they should represent the

same object, so “रथ” is “मनोरथ”, that means the real chariot and the

chariot of mind are one and the same! Isn’t it ? Or am I wrong ?

A) Here, you are applying the Rule4 to inappropriate words. The word न is an अव्यय. That means, its vibhakti-forms do not exist. Hence, instead of considering मनोरथेन alone as a single word, one must consider न मनोरथेन as a single word (because न itself has no vibhakti!) for applying Rule4. So by applying Rule4 again, we see that रथेन and न मनोरथेन denote the same object, which is true because “रथ” is indeed “not मनोरथ” !

A) Here, you are applying the Rule4 to inappropriate words. The word न is an अव्यय. That means, its vibhakti-forms do not exist. Hence, instead of considering मनोरथेन alone as a single word, one must consider न मनोरथेन as a single word (because न itself has no vibhakti!) for applying Rule4. So by applying Rule4 again, we see that रथेन and न मनोरथेन denote the same object, which is true because “रथ” is indeed “not मनोरथ” !

Q)

There is one more thing that I am not able to swallow. In the sentences

taken up by you so far, there have been no verbs ! So, are there really

no verbs in Sanskrit ? I feel like screaming, if this is true.

A) You need not scream. You are correct in that the sentences taken up so far have been verb-less, though this does not mean that those sentences had no actions involved. In fact, no sentence is possible without an action. Our sample sentences employed vibhaktis to describe actions, but actions can also be described by verbs and Sanskrit has verbal system and in fact, it is highly elaborated.

A) You need not scream. You are correct in that the sentences taken up so far have been verb-less, though this does not mean that those sentences had no actions involved. In fact, no sentence is possible without an action. Our sample sentences employed vibhaktis to describe actions, but actions can also be described by verbs and Sanskrit has verbal system and in fact, it is highly elaborated.

That’s

it for this article. In the next one, we shall explain the general

structure of a Sanskrit sentence, revealing how the tremendous amount of

Sanskrit literature ranging from Philosophy to Physics, can be

grammatically broken down into mere 2012 dhAtus and a few lone words.

PS: The definitions of vibhakti given in the article are very superficial and there are a lot many aspects to each vibhakti.

In fact, complete articles can be written on each of the 8 vibhaktis

and still may not be sufficient. The aim here is to get a new learner

started with vibaktis. For detailed learning, I would recommend checking

out other resources.